Procedural Generation Of Mazes In Unreal Engine, Part I

In the public section of AMazeGenerator class, we're now going to declare the abovementioned Width and Height properties of our maze and a starting point for the Step function, the initial values for its X and Y arguments, StartX and StartY. I'll be explaining the rest of the theory on the fly. 0. 27.

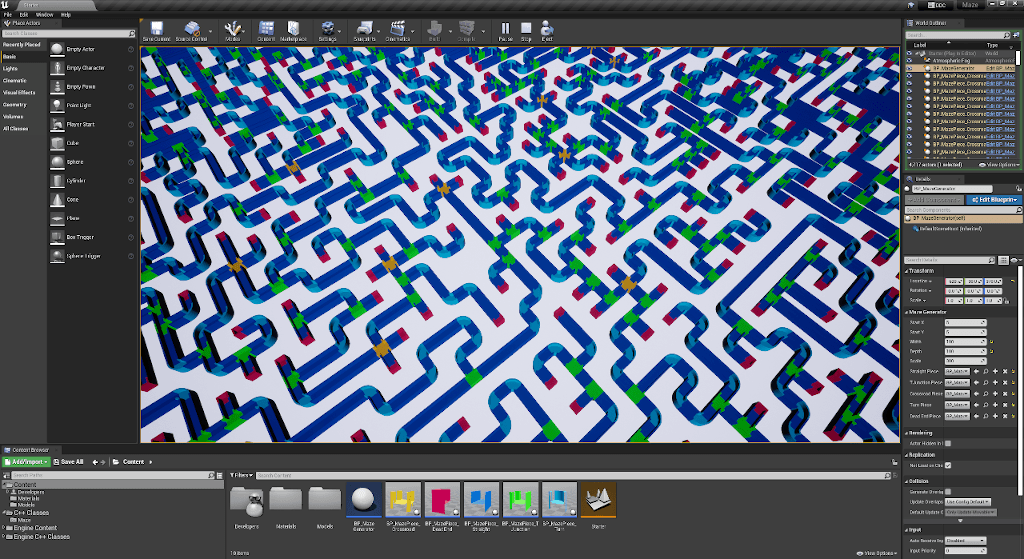

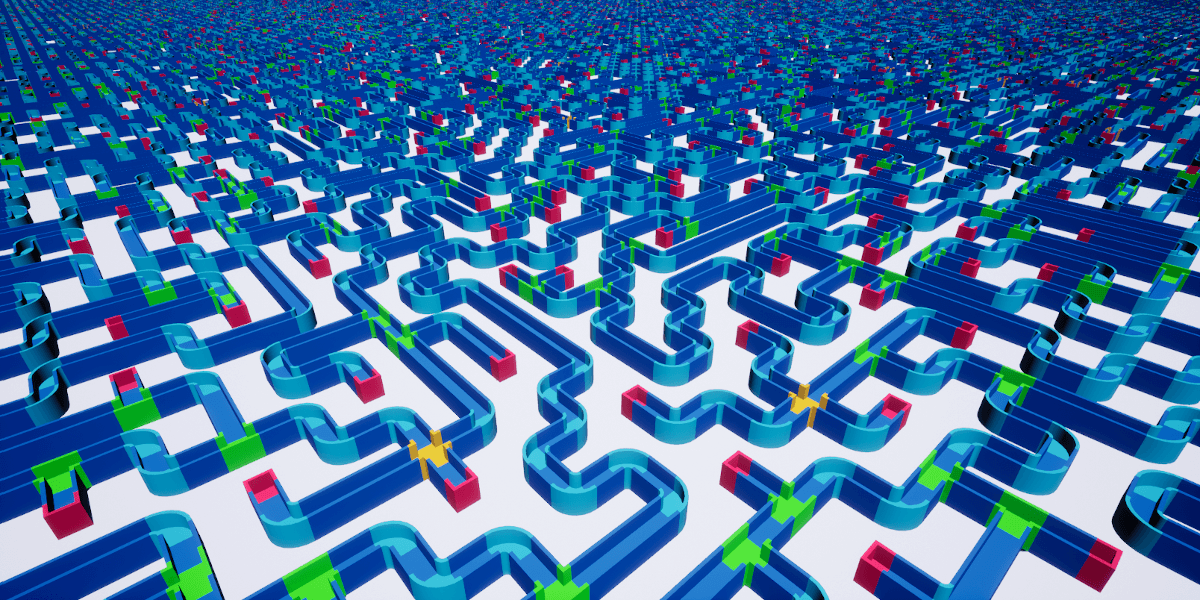

AMazeGenerator, a custom Actor class we're going to build together in this and the following part, will be able to generate a multiply-connected maze from just 5 modular pieces. By the end of the second part, we'll end up with something like this.

How To Store A Maze In Computer Memory

How To Store A Maze In Computer Memory

Before I'll tell you how I choose to represent our maze in memory, pause for a few seconds after the following paragraph, and think about how you'd do it.

Think about strings stored as an array of characters, and these characters are numbers, not actual letters, so you need an encoding table that tells you which number corresponds to which character. Can that be a source of inspiration? And how about matrices? Could a matrix be useful for us here somehow?

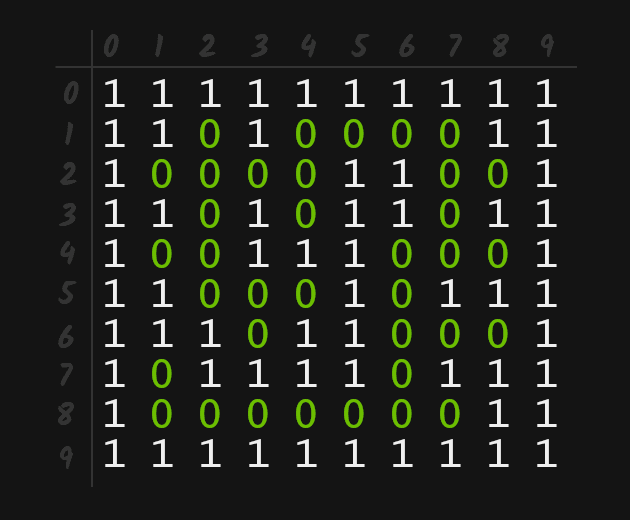

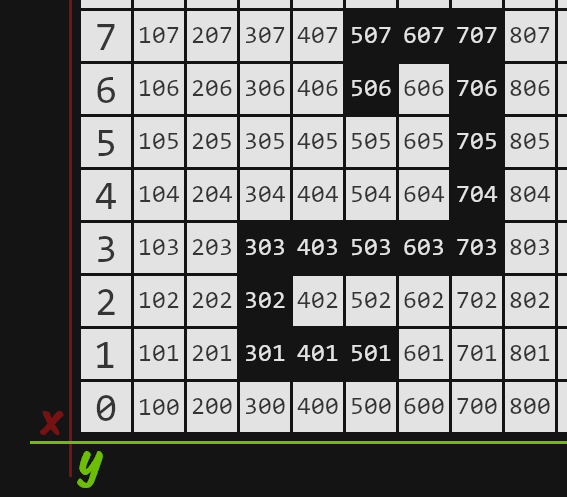

Now you're maybe thinking about storing our maze as a two-dimensional array of numbers, where 1 means wall and 0 means path and if so, well done! It's a reasonable choice if you look at the picture below.

Creating AMazeGenerator Actor Class

Creating AMazeGenerator Actor Class

Now, it's time to get our hands dirty and start building the actual maze generator. I'll be explaining the rest of the theory on the fly.

If you want to follow along, create a new Unreal project and add a new C++ class derived from Actor. Let's call it MazeGenerator.

In AMazeGenerator.h, let's declare in the protected section an inner MazeData class. As I mentioned in the previous section, this class encapsulates a Data array where 1s and 0s will represent the walls and paths of our maze.

class MazeData {

public:

MazeData(AMazeGenerator& MazeGen) : MazeGen{MazeGen} {}

void Init()

{

Data.Init(1, MazeGen.Width * MazeGen.Height);

}

int8 Get(int32 X, int32 Y) const

{

return Data[X + Y * MazeGen.Width];

}

void Set(int32 X, int32 Y, int8 value)

{

Data[X + Y * MazeGen.Width] = value;

}

private:

AMazeGenerator& MazeGen;

TArray<int8> Data;

};

MazeData Maze = MazeData(*this);

We declared TArray<int8> Data in the private section of MazeData. We also need to wire a reference to the outer class, the AMazeGenerator, itself.

Notice how we passed the reference to the outer class by dereferencing a pointer to this (*this) when creating an instance of MazeData class after the class declaration.

We pass a reference to the AMazeGenerator because we need access to its Width and Height properties when initializing Data in the Init function. And also access to Width in the Get and Set. We're going to declare these properties in a moment.

The other Init function, the one we call on Data itself, is a function of the TArray class. The first argument is the initial value of all elements. The second is the size of the array.

We set 100 and 50 as the initial values of Width and Height, so the Data array after calling the Init function will be an array filled with 5000 (100 * 50) 1s.

In the Get and Set, you can see how we get elements and set their values in the Data array using the beforementioned formula x + y * Width. The Width once again comes from our reference to AMazeGenerator.

After MazeData, let's implement another inner class, call it WorldDirections. That's the last one, I promise. I decided to implement both of them as inner classes right here to keep things simple.

class WorldDirections {

public:

void Shuffle() {

for (int32 i = Data.Num() - 1; i != 0; i--) {

int32 j = rand() % i;

Data.Swap(i, j);

}

}

int8& operator[](size_t i) { return Data[i]; }

int32 Num() { return Data.Num(); }

private:

TArray<int8> Data = { 0, 1, 2, 3 };

};

WorldDirections Directions;

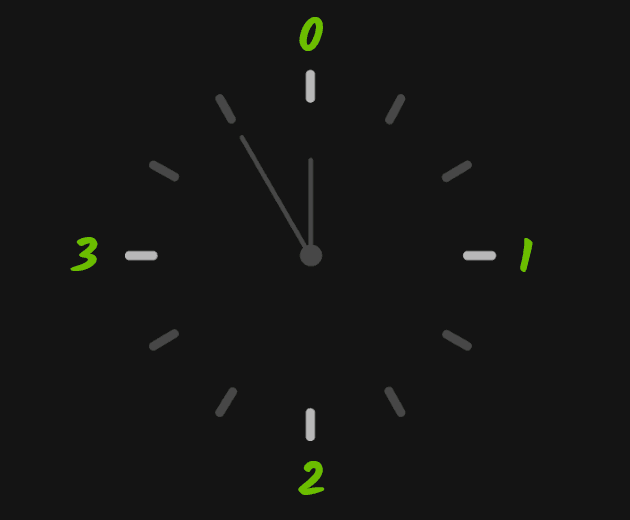

As you can see, this class encapsulates a tiny array of four numbers, each representing one of four directions – up, right, down, and left. In the left-handed Cartesian coordinate system of the Unreal world, these correspond to positive X, positive Y, negative X, and negative Y.

You may have noticed that if we put these numbers on a clock face, starting from noon and moving clockwise to 3, 6, and 9 o'clock, the directions match with directions of hands.

void Step(int32 X, int32 Y);

void Step(int32 X, int32 Y);

The Step would be a recursive function as it will directly call itself over and over, traversing our maze, initially filled with 1s, replacing those 1s with 0s, thus creating paths through until there's nowhere else to go.

We'll see that each call is a step through the just emerging maze, hence the function name, Step. I also called a similar function in another project "Dig" because when you visualize how it goes, it looks like it digs its path through initially a solid space.

In the public section of AMazeGenerator class, we're now going to declare the abovementioned Width and Height properties of our maze and a starting point for the Step function, the initial values for its X and Y arguments, StartX and StartY.

We'll also expose these members using UPROPERTY macro, so we can later change these values in the editor.

UPROPERTY(EditAnywhere)

int32 StartX = 5;

UPROPERTY(EditAnywhere)

int32 StartY = 5;

UPROPERTY(EditAnywhere)

int32 Width = 100;

UPROPERTY(EditAnywhere)

int32 Height = 100;

Now, let's switch to MazeGenerator.cpp and in the BeginPlay function, first, initialize our Maze and right after that call the yet not implemented Step function, passing the initial StartX and StartY values.

void AMazeGenerator::BeginPlay()

{

Super::BeginPlay();

Maze.Init();

Step(StartX, StartY);

...

You're now may be asking why we're not initializing our array in the MazeData constructor, and that's an excellent question. If we've done so, we'd introduced quite a nasty bug.

Our code would initially work as expected. The problem will occur only when we'd increase Width and Height properties in the editor. Maze Data array would be already initialized, with smaller (!) values (default Width and Height from AMazeGenerator and we'll eventually try to access data outside the upper bound of the array. When this happens, the editor crashes, throwing IndexOutOfBoundsException.

It will be clearer from the Step function that we'll implement now. First, I'll paste here the entire implementation. Take a brief look at it, and then I'll explain the algorithm step by step.

void AMazeGenerator::Step(int32 X, int32 Y)

{

Directions.Shuffle();

for (int32 i = 0; i < Directions.Num(); i++) {

switch (Directions[i])

{

case 0: // Up

if (X + 2 >= Width - 1 || Maze.Get(X + 2, Y) == 0)

continue;

Maze.Set(X + 2, Y, 0);

Maze.Set(X + 1, Y, 0);

Step(X + 2, Y);

case 1: // Right

if (Y + 2 >= Height - 1 || Maze.Get(X, Y + 2) == 0)

continue;

Maze.Set(X, Y + 2, 0);

Maze.Set(X, Y + 1, 0);

Step(X, Y + 2);

case 2: // Down

if (X - 2 <= 0 || Maze.Get(X - 2, Y) == 0)

continue;

Maze.Set(X - 2, Y, 0);

Maze.Set(X - 1, Y, 0);

Step(X - 2, Y);

case 3: // Left

if (Y - 2 <= 0 || Maze.Get(X, Y - 2) == 0)

continue;

Maze.Set(X, Y - 2, 0);

Maze.Set(X, Y - 1, 0);

Step(X, Y - 2);

}

}

}

It's the essential logic of today's part. So what's going on here? First, we shuffle our Directions.

Directions.Shuffle();

After that, the Data array of the Directions class can have its elements shuffled, for example, like this.

{ 0, 3, 1, 2 } // Up (+X), Left (-Y), Down (-X), Right (+Y)

Let's now continue further down the Step function execution. We see a for loop over our just shuffled Directions, and in this loop is a switch statement for each possible value, each direction.

for (size_t i = 0; i < Directions.Num(); i++) {

switch (Directions[i])

{

...

In the first iteration, the index i is 0, and the first element of Directions, the one at index 0, has a value of 0 (up, or X+). The switch falls into the first case.

case 0: // Up

if (X + 2 >= Width - 1 || Maze.Get(X + 2, Y) == 0)

continue;

Maze.Set(X + 2, Y, 0);

Maze.Set(X + 1, Y, 0);

Step(X + 2, Y);

Here we have an if statement where we first check if we're close to the edge of our maze. To be precise, the two steps below the upper edge. Then we check if at position two steps in the up direction is already a path (0 is a path, 1 is a wall).

The Width and Height of our maze are both set to 100, and X and Y are our initial values of StartX and StartY, which we both defined in MazeGenerator.h to be 5.

Let's plug in these numbers and solve these expressions by hand. The first one is simple.

5 + 2 >= 100 - 1

7 >= 99

false

No, the number 7 is not bigger or equal to 99. We're not too close to the upper edge. In fact, our starting position { 5, 5 } is on the opposite side, close to the bottom left corner.

For the subsequent expression, we remember what's going on in Maze.Get(X,Y) is return Data[X + Y * MazeGen.Width] so we can expand and solve it like this.

Data[(5 + 2) + 5 * 100 + 5] == 0

Data[705] == 0

1 == 0 // We know that our MazeData::Data array we have filled with 1s.

We initialized it as such in BeginPlay.

false

Both expressions are false. We don't branch to the continue; statement. Instead, we set two adjacent elements up from our starting position to 0, and we call Step function within itself (recursion) with new values.

Let's once again plug in the actual values and evaluate expressions.

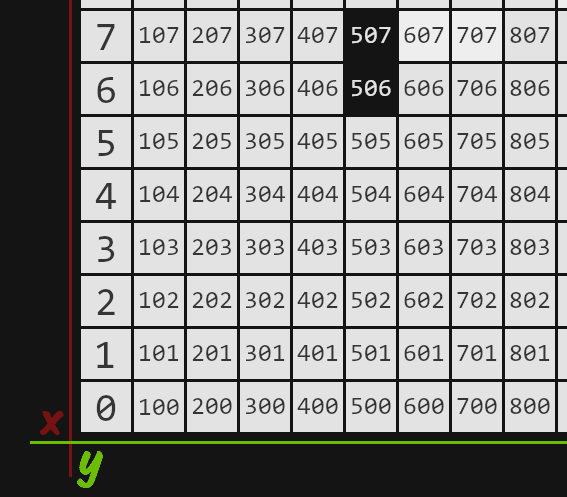

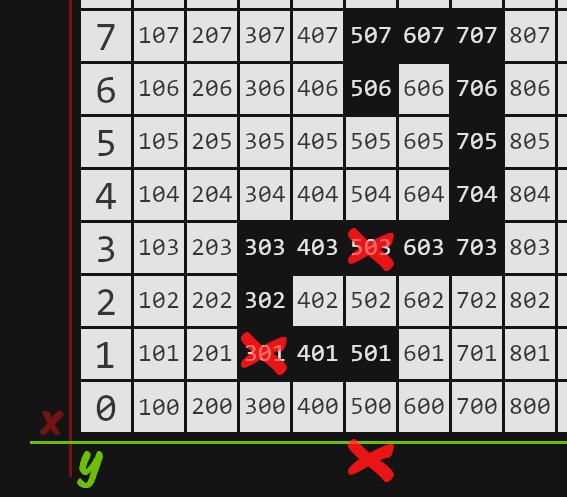

Maze.Set(5 + 2, 5, 0); // => Data[(5 + 2) + 5 * 100] = 0 => Data[507] = 0;

Maze.Set(5 + 1, 5, 0); // => Data[(5 + 1) + 5 * 100] = 0 => Data[506] = 0;

Step(7, 5); // (5 + 2, 5)

This picture illustrates the current state of the small part of our maze array around the starting position { 5, 5 }, which is the item with index 505.

{ 1, 0, 2, 3 } // Right (+Y), Up (+X), Down (-X), Left (-Y)

{ 1, 0, 2, 3 } // Right (+Y), Up (+X), Down (-X), Left (-Y)

With these values, the execution will look almost the same. The only difference would be in the direction. This time, we'd fall in the switch statement into a case for value 2 (right direction, +Y), and in the end, the elements 707, and 607, will be set to 0, and new parameters we'll pass to the Step function will be 7, 7.

Instead of explaining the same thing again, let's skip a few steps and imagine our maze is now in the state that illustrates the following picture.

{ 0, 2, 3, 1 } // Up (X+), Down (X-) , Left (-Y), Right (+Y)

{ 0, 2, 3, 1 } // Up (X+), Down (X-) , Left (-Y), Right (+Y)

We again fall in our switch statement in the case for value 0. Let's expand and plugin values into our if statement as before. The first expression is:

1 + 2 >= 100 - 1

3 >= 99

false

Of course, we're almost at the very opposite side of our maze. We cannot escape the maze by going just two steps up. But what about the second expression?

Data[(1 + 2) + 5 * 100] == 0

Data[503] == 0

0 == 0 // We can see that element at index 503 is already set to 0.

true

Aha! Now we have false or true, which evaluates as true. We branch and hit...

continue;

We're at the top of our switch statement, but this time, we take the value of the second element from the Directions array, which is number 2 (Down, -X), so we end up in the following case.

case 2: // Down

if (X - 2 <= 0 || Maze.Get(X - 2, Y) == 0)

continue;

Maze.Set(X - 2, Y, 0);

Maze.Set(X - 1, Y, 0);

Step(X - 2, Y);

You already see, what's going to happen, right?

1 - 2 <= 0

-1 <= 0

true

We don't even need to evaluate the second expression. We know we can't go down because we'd end up outside the maze, thus outside the array, throwing an IndexOutOfBoundsException.

To be continued...

To be continued...

In the next part, we're going to use the memory representation of a maze in the subsequent process when we use clever pattern matching for building a maze out of modular pieces, just like the one you saw in the first image at the beginning of the post or the ones n the screenshots below.

See you in the Part II!

Width = 20, Height = 50

Width = 20, Height = 50